(Editor’s note: Bob Coldeen has been a long-distance collector pal of mine for a few years, and I have always appreciated his many stories about how he acquired his autographs as a kid, including but not limited to while serving as spring training bat boy in the 1960s. Enjoy these stories from Bob, one at a time in three installments!-Matt)

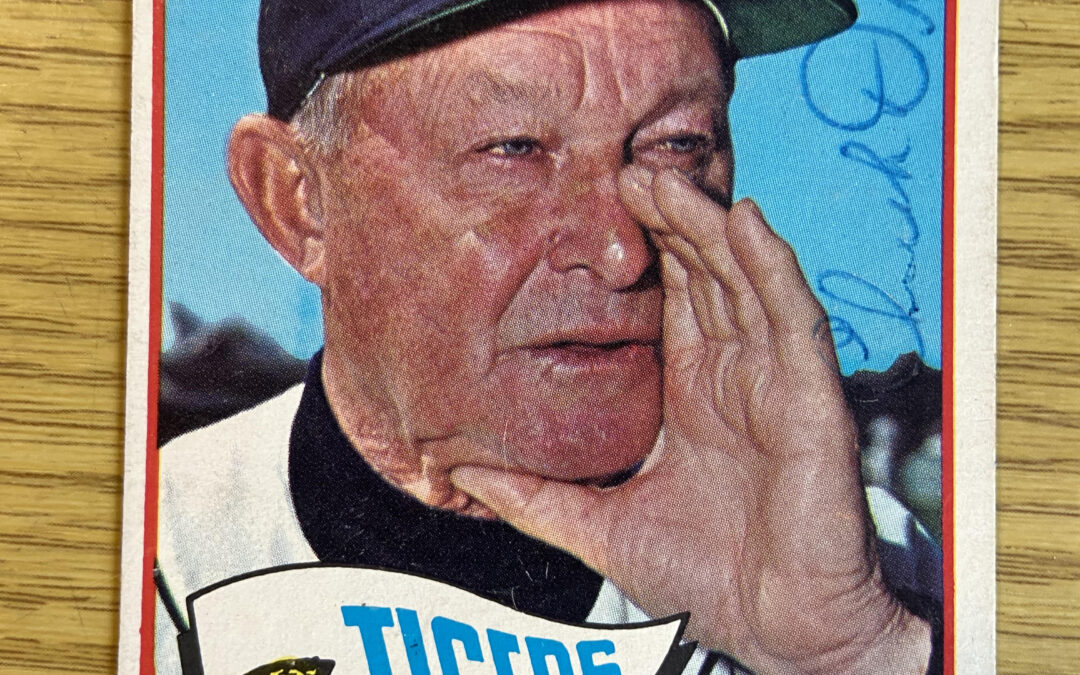

Me, Red, and Chuck Dressen

My grandfather drove me and my mom in his 1956 Buick Century up Florida Avenue, past Memorial Boulevard, to Henley Field for a spring training game.

Henley Field had been spring training home for the Detroit Tigers since 1934. I heard that Babe Ruth once hit a home run over the forty foot fence in centerfield 405 feet away. Ted Williams, Lou Gehrig, Joe DiMaggio ran around the bases there. So did Mickey Mantle and Hank Aaron.

Thanks to my mom’s connection, I got to be a batboy for the Tigers that day. She walked me over to the home dugout and said to whoever was listening that I was their batboy and left to sit in the grandstand.

An older, diminutive man came over and I introduced myself. Chuck Dressen welcomed me and then quickly moved to more important things. The smallest guy in uniform, a boisterous field general, left no doubt who was in charge of everything.

As a player on the 1933 New York Giants, he helped win Game 4 of the World Series despite not playing. Up by one run in the 11th inning, the Senators had the bases loaded with one out and Cliff Bolton pinch hitting. Dressen, on the bench as a reserve player, called time from the dugout and ran out to the mound. He had played with Bolton in the minor leagues and told the pitcher how to pitch to him. Bolton hit into a game-ending double play and the Giants went on to win the Series.

The Tigers manager, who also managed the Dodgers with Jackie Robinson from 1951-53, was featured in the classic book The Boys of Summer where Roger Kahn related a colorful story of Dressen schooling a young baseball writer.

None of that I knew while standing there in the dugout with Al Kaline, Norm Cash, Bill Freehan, Denny McLain and the rest of the team.

The other batboy was Red, called that for his red tinged hair. Same age as me, he darted around the field, handing out gloves, picking up balls, arranging bats, always a step ahead of me.

Dressen took me aside, and scolded me with a stern reprimand. No one had talked to me quite like that as I had grown up a model student in a lenient, fatherless home.

Dressen looked me square in the eyes and said, “Son, if you are ever going to be anything in this world, you have to know what you are supposed to do and then do it.” I was taken aback.

At the age of 13, I had skated through life basically without rebuke. That upbraiding woke me up to the reality that I was not perfect, and worse, that I was failing.

Two days later Dressen suffered a heart attack and left the team. He died the following year on August 10, my son’s birthday.

Over the next three seasons, I would see Red outside the ballpark, snagging foul balls and selling them to boys too slow or lazy to get them.

I stopped buying baseball cards and going to games my senior year of high school. I forgot about Red and Dressen until one day at home visiting from college, I read in the newspaper that Red had been arrested for selling cocaine.

The memory of that one afternoon at Henley Field flooded my consciousness, reminding me of the life-long lesson Dressen had given me straight, how he schooled me like he had schooled that young reporter in bygone days, and how life turns on the simple question, “What are you supposed to do?”