Foreword

I made a new friend at the National this year. Angel is from Puerto Rico, and he was kind enough to share with me a draft of his amazing Toleteros book in progress. In case you’re not familiar, Toleteros were Puerto Rican cards first issued in the 1948-49 winter season of the Puerto Rico Professional Baseball League. One set contains the only known standard-issue “card” of Negro League great Josh Gibson. Though a posthumous release, it is one of the grails of Negro League collecting. (If you would like to read the gripping tale of the discovery of the Gibson cards, and see more fantastic images, read my favorite guest-authored Cardhound article here).

They are amazing, rare cards that also give insight into a culture of racially-integrated baseball that was commonplace nearly everywhere but the United States, as early as the turn of the 20th century. Many Americans don’t realize this, and instead assume that racial segregation was the cultural norm elsewhere as it was here. It was not.

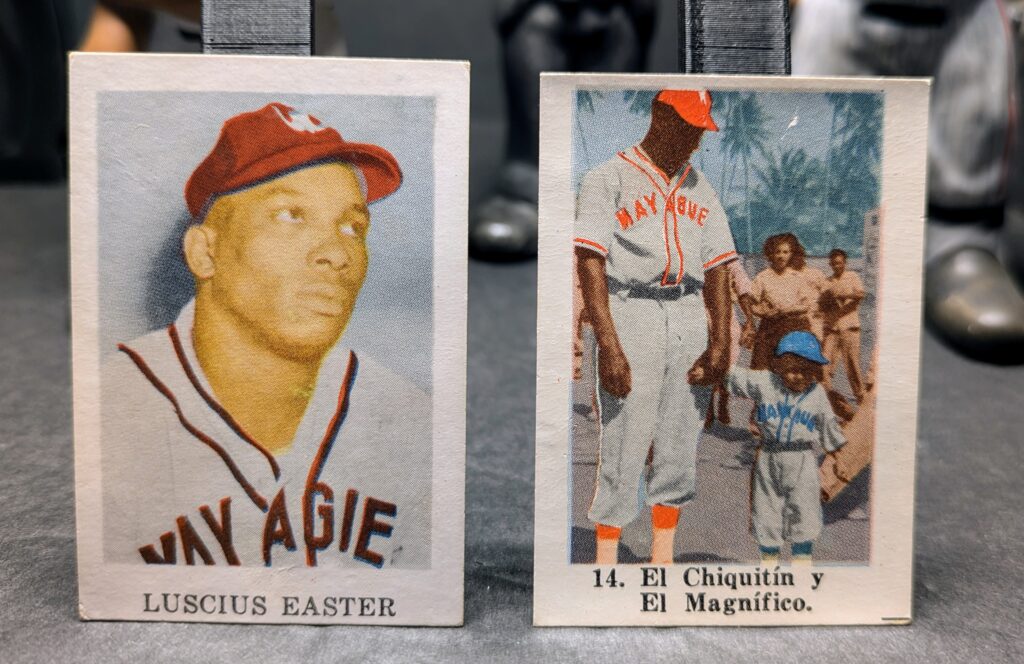

(photo: Ryan Christoff)

Since I collect mostly Cuban cards of Negro League players, I was of course interested in his book, his store of knowledge, his passion for collecting, and in the amazing collectibles he had in hand that day. I have since helped with some light editing of the book–now off to print!–and for those efforts he was kind enough–too generous–to send me two cards I have been hunting for like a needle in a haystack for the past few years. Check out these Toleteros cards of Negro League great and solid MLB player Luke Easter. I’m honored to add them to the permanent collection.

Just today, Angel contacted me with an outline and some article ideas, and I offered to turn them into an essay. The intersection between race / racism and collecting is complex territory to navigate, but Angel and I both agreed that the recent record-breaking sale of the Jordan / Bryant 1/1 dual logoman card was significant not only for the astronomical sum it fetched, but also because it is the first time a non-white sports star (or, two) has owned top billing in the hobby in terms of value. Move over Honus and Mick. It is at the least a development worth acknowledging and discussing.

So, the following represents a mishmash of collective thinking about why this sale is perhaps significant for the hobby beyond just dollars and cents.

Race, History, and Sports

Vintage sports collecting has long been celebrated as a way of preserving history, nostalgia, and cultural identity through tangible artifacts like cards, programs, and memorabilia. After all, without the cultural attachments, it’s just paper and cardboard.

But the history of our hobby is also a history of race and racism and, by extension, (under)representation. For decades, Black athletes were under-documented, under-valued, or outright excluded from mainstream collecting markets, even as they broke barriers on the field. Negro Leagues were quite popular in the United States, but no company seized on this opportunity to legitimize the Leagues with trading cards. Most trading cards in the early 20th century were distributed through consumer products like tobacco, caramel candy, or gum—industries that marketed heavily to white buyers.

Companies weren’t motivated to feature Black players likely because they didn’t believe there was a profitable market among white consumers, and systemic racism meant they didn’t see Black consumers as a target market either. The lack of cards also reflected a larger pattern: mainstream media and cultural institutions often minimized or ignored the accomplishments of Black athletes outside of MLB. Just as newspaper coverage was inconsistent, their presence in collectible culture was nearly nonexistent.

It’s a touchy conversation for many, but while it’s arguable that Mickey Mantle holds such hobby market value because he was “the best player on the best team,” that alone does not explain Mick’s hobby dominance over, say, Willie Mays. Certainly, most fans and collectors were white (it’s just math + marketing), and Mantle had that undeniable small-town charisma that was relatable to most Americans. He also had prodigious power, speed, and ability that were not at all relatable. Combined with the championships, the MVP’s, and the “what if?” mystique regarding his bum knee, Mantle has all the elements of an enduring GOAT legacy. It’s a deserved legacy.

But also keep in mind that even though Jackie “integrated” MLB in 1947 (followed closely by Doby’s integration of the AL), Boston did not sign its first Black player until “Pumpsie” Green in 1959. The league was hardly “integrated” for the first half of Mantle’s career, and Black players were underrepresented for decades after.

In today’s hobby, items tied to the Negro Leagues, barnstorming tours, or international leagues where Black players found opportunity stand as both hobby treasures as well as contested commodities, depending on who you ask. This seems especially true in the last year, in the wake of MLB’s decision to recognize Negro Leagues as Major Leagues, a move that both ignited praise and sparked debate. But like with lots of other vintage this year, Cuban cards of Negro Leaguers are also having a moment in terms of record-breaking sales.

Race and Collecting

As a white guy collecting mostly Negro League players, it has been suggested more than once in unsolicited comments that my entire collection is a function of “white guilt.” It has always been intended as an insult, but I guess I don’t entirely disagree. I have always been interested in digging up the untold story, the counternarrative, the underdog tale. If “white guilt” means feeling unsettled about historical or ongoing racial injustice, I guess that’s me. All Americans should feel unsettled about the racist past of this country–the other options are not very appealing.

And I’m certainly not alone. It’s that impulse that can push someone to educate themselves, to truly listen, to act in solidarity, to be an ally, an advocate. As a teacher (college professor) of mostly students from marginalized groups (whether racial or economic or sexual orientation or dis/ability), relating to others who are in many ways not like me is my day job. I don’t “apologize” for the racist past because it’s not my past. But I recognize the position and opportunity that have been granted to me in large part because of my race (and also my gender and my social class, growing up in safe communities with good schools and an upper-middle-class two-parent household). Yes, I have also worked hard for whatever success I’ve had in life–privilege and hard work are not mutually exclusive, nor do they always correlate.

As interest in Negro League and vintage sports collectibles in general continues to grow, we are presented with opportunities and perhaps a responsibility to confront how issues of race and historical recognition (or lack thereof) shape not only the stories we choose to preserve but also the value we assign to them–past. present, and future. The Jordan / Bryant record sale is not necessarily a direct descendant of the conversation above–but it might be.

So now we take a turn back to Angel’s notes and interest in the Jordan / Bryant sale and how it relates to the above conversation:

A New Era of Record-Setting Sales

The aforementioned Jordan / Bryant 1/1 broke records this August when it sold for $12.932 million at a Heritage Auctions Platinum Night event—the highest price ever paid for a sports trading card.

Previously, the record-holder had been a 1952 Topps Mickey Mantle card, which fetched $12.6 million in August 2022. The Jordan–Bryant card now stands as the most expensive sports collectible card ever sold. Overall, it ranks second only to Babe Ruth’s 1932 “called shot” jersey, which sold for $24.12 million in 2024. This sale isn’t just staggering financially—it signals a potential cultural shift. The legacies of Jordan and Bryant, and by extension the NBA, are being valued like never before. How might the impact of this momentous sale “trickle down” into the hobby?

The Historical Imbalance in Collectibles

For much of the 20th century, sports collecting was shaped by baseball’s dominance. Cards of mythic (and, notably, White) figures like Honus Wagner, Babe Ruth, and Mickey Mantle defined the hobby. Meanwhile, Black athletes—even those as transformative as Jackie Robinson, Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, or Bill Russell—often received less financial attention. This was a reflection, in part, of aforementioned societal inequities that extended into the collectibles market. It’s nonsense to claim otherwise: the racism that prevented Negro League card sets in the first place did not just magically disappear.

But it is also fair to note that since integration came late to most sports in America, there are very few prewar icons to chase of Black players, and thus most Jackies and Aarons are not especially rare except in high grades. The great Josh Gibson only has that one issued “card”—and it is neither American nor playing days. A true Josh Gibson “rookie card” would surely compete with all the other legends of the game in terms of value. And even as it sits, the Gibson card will most often be a 6-figure card going forward.

Ironically, it is perhaps the rise of global basketball, not baseball, propelled by Jordan and later Kobe and LeBron James, that began to alter the narrative. Now, with a Jordan–Bryant card commanding double-digit millions, the emotional and cultural value of Black athletes is being more fully recognized both culturally and financially.

Basketball’s Global Influence and Collectible Power

Basketball’s appeal spans continents in a way baseball never achieved. Michael Jordan’s ascent in the 1990s, bolstered globally by NBA sponsorships and media, redefined what it meant to be a global sports icon. Kobe Bryant extended that reach into the new millennium. Today’s high-end collectors are drawn from Asia, Europe, the Middle East, and beyond, elevating the value NBA collectibles. (Note: the Jordan-Bryant buyers are ultra wealthy American White guys).

While baseball is also an increasingly diverse international game, the hype and global fame have not followed suit as for NBA players. And notably, the MLB draws many of its players from poor lower-income countries like Cuba and the Dominican Republic. Ohtani in an exception, and is unquestionably the game’s most marketable star currently on the global stage. Basketball also has the advantage of smaller rosters and fewer players, making the biggest stars easier to watch and follow.

Opening the Door for the Negro Leagues and Beyond

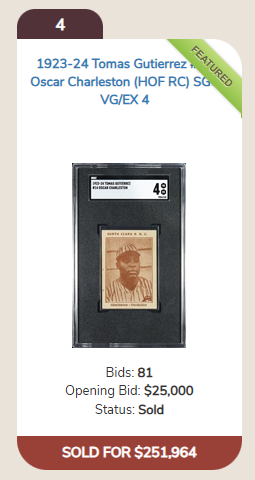

As Jordan and Kobe command auction headlines, attention is also turning toward legends who were historically overlooked—including those from the Negro Leagues. These players’ stories are finally getting their due in both cultural and market terms. A striking recent example: an Oscar Charleston Cuban Winter League card—a scarce issue from 1923–24—sold for $251,964, marking a record for a Negro League card. With only nine graded specimens known, the scarcity and historical significance of this card pushed demand to new heights, perhaps bolstered by MLB’s recent recognition of Negro Leagues as “Major Leagues.”

Charleston, often dubbed the “black Babe Ruth” or “black Ty Cobb,” was celebrated for his power at the plate, speed on the bases, and defensive prowess. That his card is now commanding six-figure sums reflects a growing collector interest in these athletes whose greatness was overshadowed by segregation in the U.S. Combined with the fact that many cards of Negro Leaguers are ultra-rare issues originally circulated not in the United States mainland, but instead to commemorate winter leagues in Cuba, Venezuela. Mexico, and Puerto Rico, the market for these cards may be just getting started. The value equation in vintage is generally scarcity + interest, aka supply and demand. These cards have always been scarce, and any new collector interest will strain the incredibly small supply.

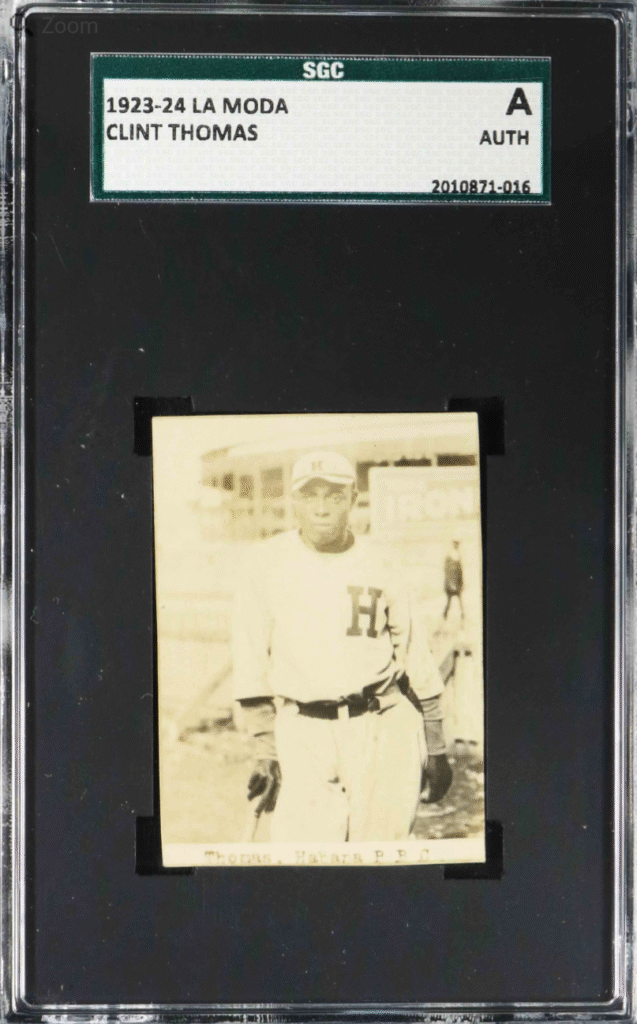

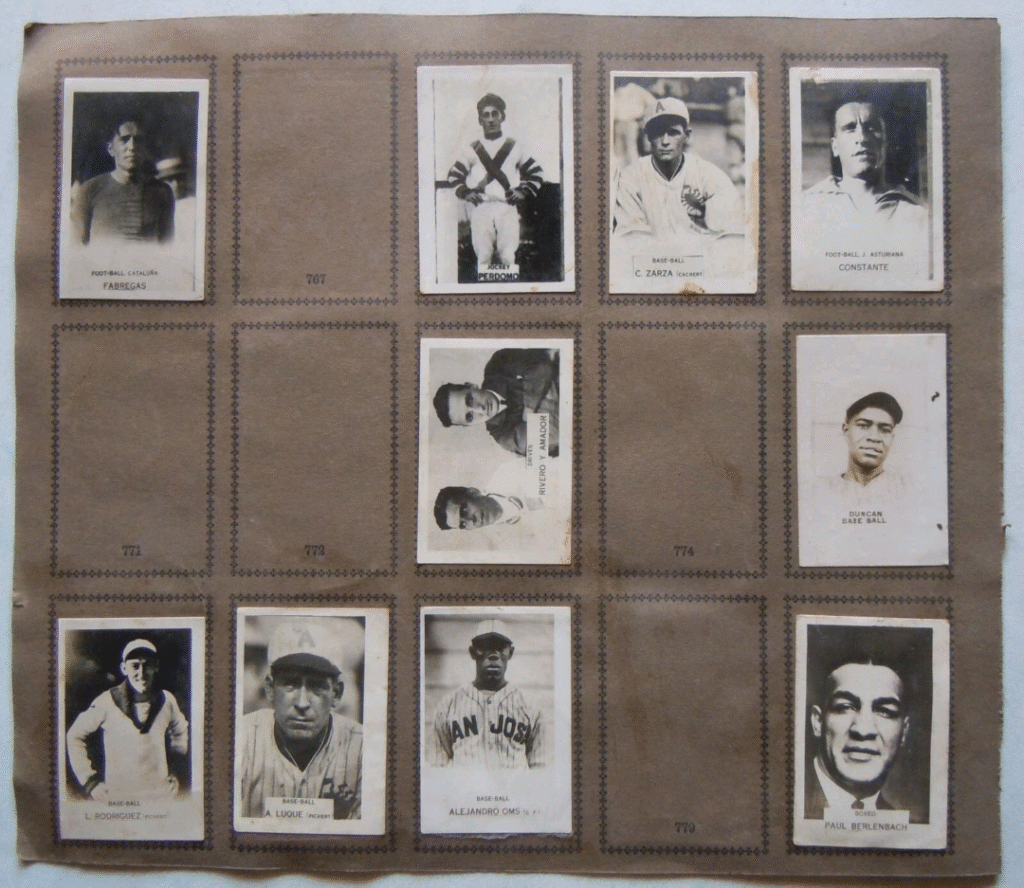

I will never own that Charleston, but I do enjoy chasing rare cards of other talented players of his era, such as American Clint Thomas and Cuban Alejandro Oms.

(A true 1/1 to date, this is the only known example of this particular card)

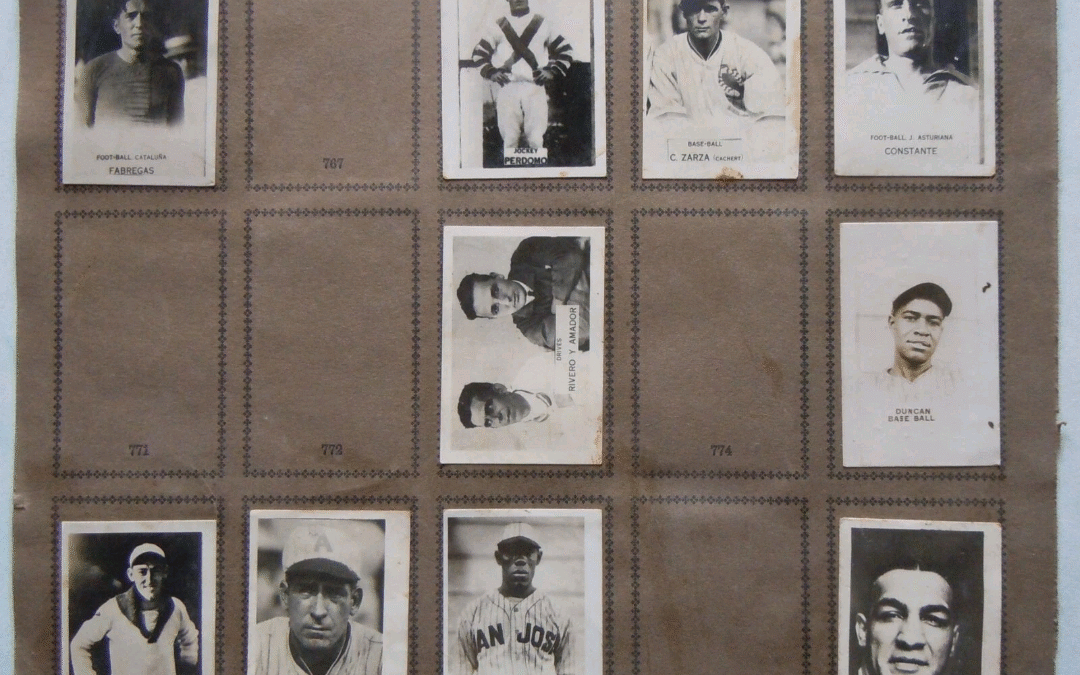

(Finding rare intact album pages like this one is what I live for, in the hobby sense)

The Road Ahead

Monetary value in collecting is always a mirror of cultural perceptions–and cultural perceptions are always shifting, if slowly at times. Just as Wagner, Ruth, and Mantle defined the mythology of sports collectibles until now, Jordan and Kobe—global icons with transcendent appeal—might be shaping its future, with Ohtani not far behind. As their cards break price ceilings, we’re witnessing not just economic peaks, but a broader cultural restoration: long-overdue recognition of Black and non-White athletes’ rightful place in sports history.

That restoration is vital to history and to the hobby. Whether it’s Negro Leagues stars, early NBA legends, or pioneers in other sports, higher visibility and record-setting sales drive both archival interest and investment. Cards transcend the paper on which they are printed—they become iconic symbols of what matters culturally and historically.

Years from now, the Jordan–Bryant sale could be remembered as a turning point—not merely for basketball cards, but for the entire hobby. As collectors chase rarities and legacies, they may seek Jackie or Josh or Oscar Charleston with equal reverence and financial interest. You might disagree, but it seems like this sale has blown open a door that has been only ajar for too long.

Such a great Race and Sports essay!

Your style on expressing the ideas are super.

I enjoyed this article.

Keep on going, my friend.

Man,it is so nice to keep reading well researched(and WELL WRITTEN) articles on collecting,Matt…keep up the fine work!..Craig